We have all heard horror stories about the builder who takes a deposit and never does the work and never shows up again. This is usually preventable.

It starts with vetting. It may seem obvious, but research your builder. Not a little. Research A LOT. Really try to unearth who this person and company is. Start with checking basic licensing with the Secretary of State to ensure they are licensed and bonded. You can search by name and company. Next check the department of labor and industries. This is where they list any previous safety infractions that were violated. Next dig deeper and look into the personal assets of the builder to see if there are any judgements or liens against them. This can be done by researching public records at the county recorder’s office. This is usually all online. All these things will disclose the accountability of the builder. Sure, do the obvious and check the website for examples of previous work and ask for referrals. Here you are sure to see prefiltered examples of the builder’s best work they have ever done. This is the best you can expect to get for your project. Lastly, do a bit of social network research on this person. Before hiring them on the biggest expense you will ever have, it makes sense to know everything you can.

Now you are equipped to interview your builder before deciding to hire them. This gives you and the builder a chance to discuss the information you found, and this is for you to decide if they pass your smell test. You will be working together on the biggest investment you’ll ever make for over a year likely. Make sure you LIKE this person.

Next it’s time to lay the ground rules for how you will be working together. This gets complicated because most homeowners have never had to negotiate with a builder before, and the builder surely has some established protocols they use and prefer (because it benefits them). There is a lot about the construction process that most people are just not familiar with, so relying on your architect (and maybe an attorney) is crucial in reviewing the contractor’s contract and also laying out the ground rules on HOW you require them to bid your project. You do not want to be in a situation where your project is almost done except for a few unfinished (or improperly finished) areas and the builder is requiring you to pay for them - or even worse: you already paid for them. There are some typical checks and balances that you need to be aware of that your architect can help setup at the start of the project.

Similar to dining out at a restaurant, you don’t pay for your meal (and service) first. No, first you get the service, THEN you DECIDE how much it was worth. This is somewhat similar to construction. There is a menu of items that need purchased and assembled, and there is a price tag for each. This menu is your bid and construction contract. The more detailed the bid, the more you will understand what you are ordering and should be getting. For example, there should be a line item for drywalling. The builder should not bill you for that until you have received it. This means the materials need to be ordered, delivered, and on site (stored properly according to manufacturer instructions). And it needs to be properly installed according to manufacturer’s instructions AND contract drawings prepared by the architect. If it is not done accordingly, you should not be entitled to pay for all of it. Similar to a restaurant, you have the opportunity to accept your meal to ensure it is what you ordered before you eat it and pay for it. In construction it is similar, but to keep things fair for the builder, they should be able to bill you in increments - usually monthly - for the items completed based on a percentage of completion. Again, this is where your architect comes in handy. The architect is a third party who is very versed in what is supposed to be built, how it is supposed to be successfully constructed, and has a thorough understanding of the contract language on typical construction documents.

Your builder should submit an “application for payment” to the architect every month for review. On this payment application, they should list out the items that appeared on their bid that you expected to pay. On each line item, they should list a good faith percentage of completion. Your architect should have a walkthrough with you and the builder to review the work to ensure those percentages reflect the actual work completed, so your builder can be paid for their successful efforts. Any work that is not completed according to the contract drawings should not be paid for until it is completed properly. Your architect will request you withhold certain portions of any payments that still require more work, and the architect will explain this to the builder. This often involves faulty workmanship, so a creative strategy will be needed to get things back on track. The architect is the best party to oversee this since the homeowner is typically not aware of faulty workmanship, and the builder has a financial incentive to build things cheap and fast to get their payment faster. This results in corners being cut that you hear about so often. Having a portion of the payment withheld will provide incentive for you and your architect to motivate the builder to complete any loose ends and to discuss a strategy to do it.

Establishing this protocol early in the build (like before it starts), is important to create a transparent working relationship and to clearly communicate that you expect to pay for the work that is completed according to your plans - and nothing more.

Most of the builders out there are good, but the few bad ones make a bad name for everyone unfortunately. The good builders own up to their own mistakes usually, and they correct them without being asked. Developing a good working relationship with your builder is key to ensure mutual respect in how you work together and pay one another when there are gray areas.

Some builders will require payment for portions of work up front. This is called a retainer. This is perfectly normal and acceptable IF executed properly. This retainer effectively guarantees that the homeowner will not stiff the builder. The builder will withdraw money from that retainer as the work is successfully completed or just hold it until the end of the project to protect themselves if a client decides not to pay an invoice. Before you pay a retainer for work not yet completed, be sure you trust your builder, be sure the terms of payment and refund of the retainer are 100% clear, and be sure the retainer amount is not exceedingly large. It really only needs to cover the operating expense of the builder, so they can pay their overhead and crew and purchase the needed materials while waiting for the next progress payment. Anything more than that is questionable.

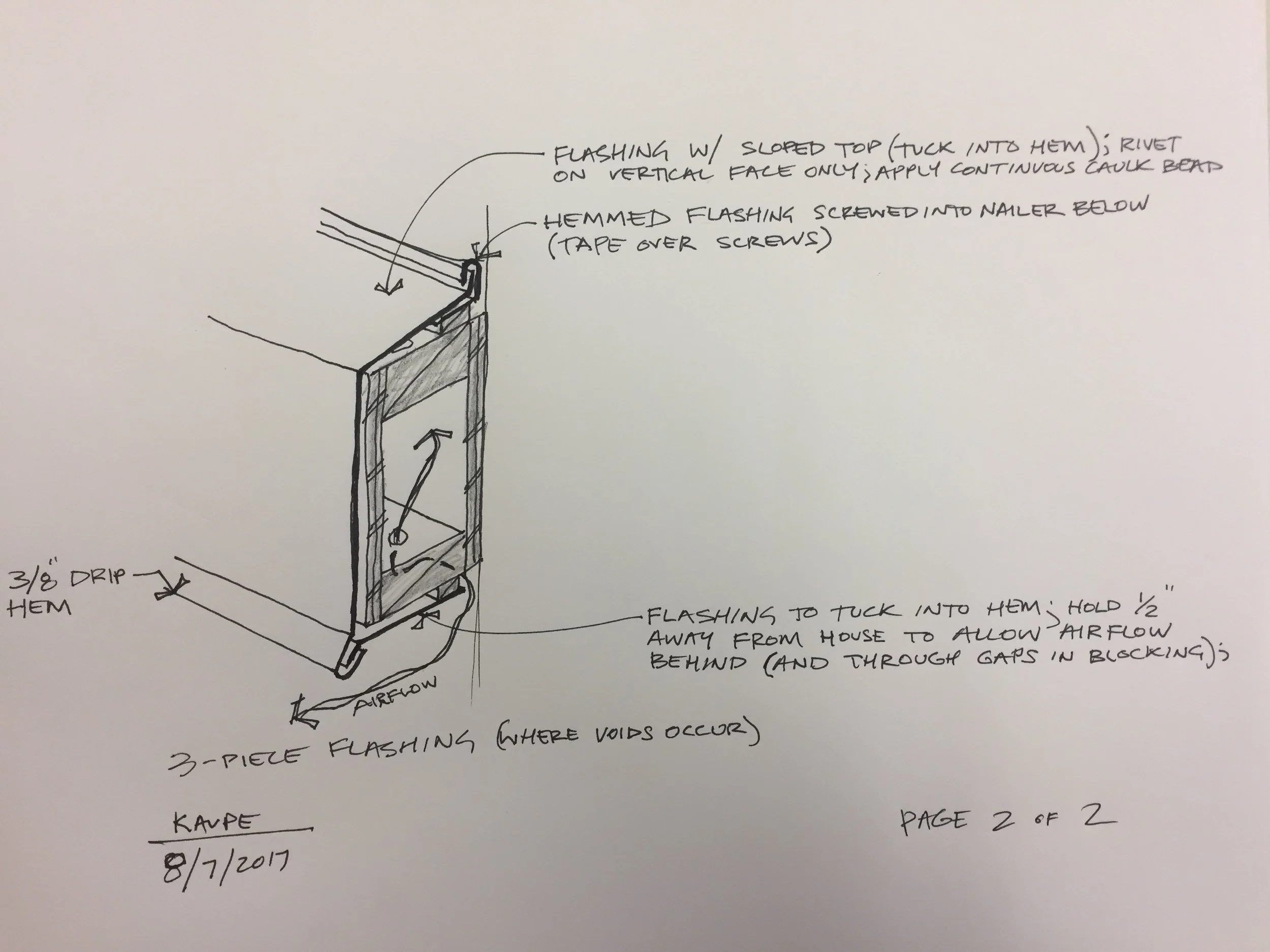

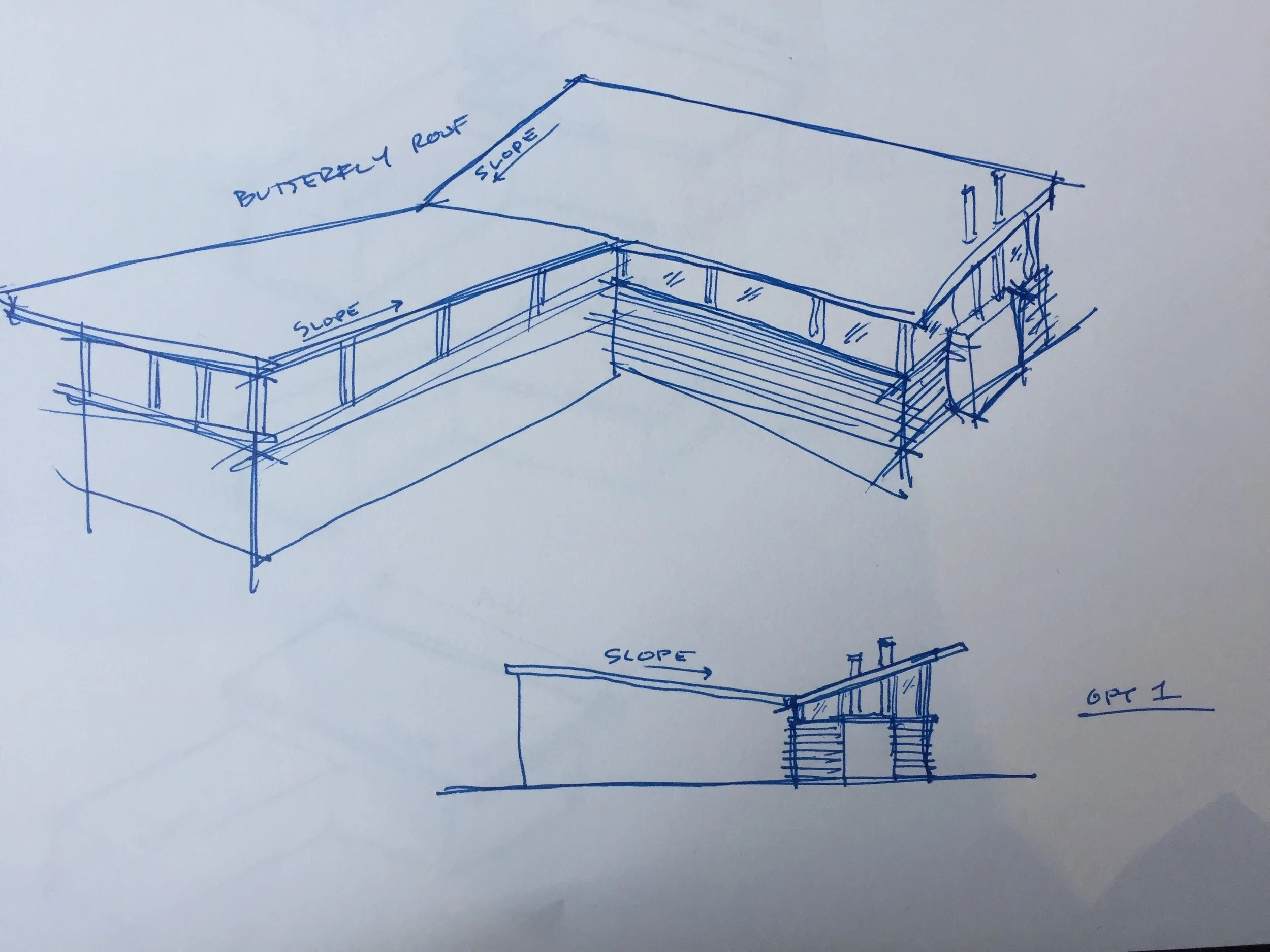

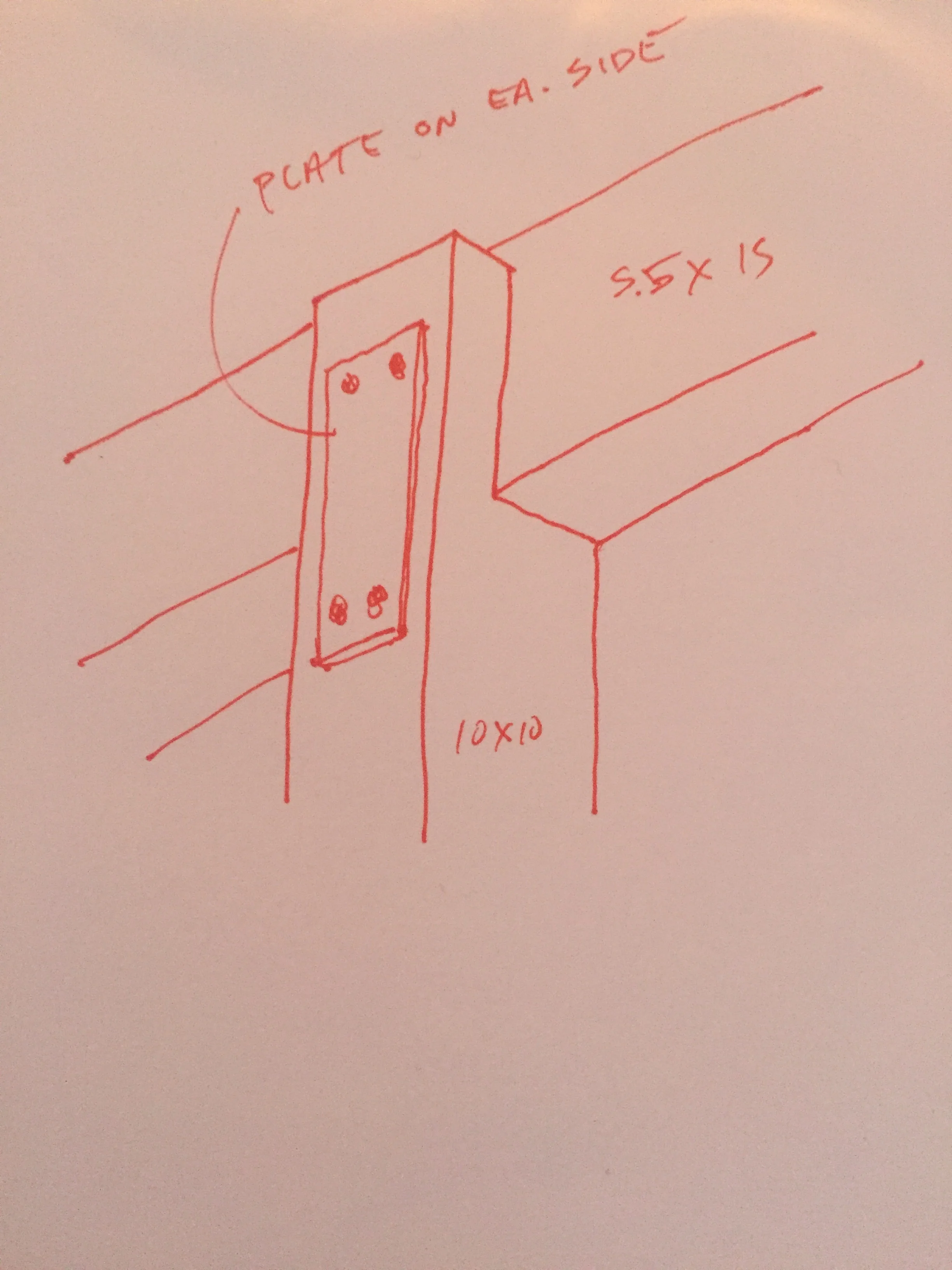

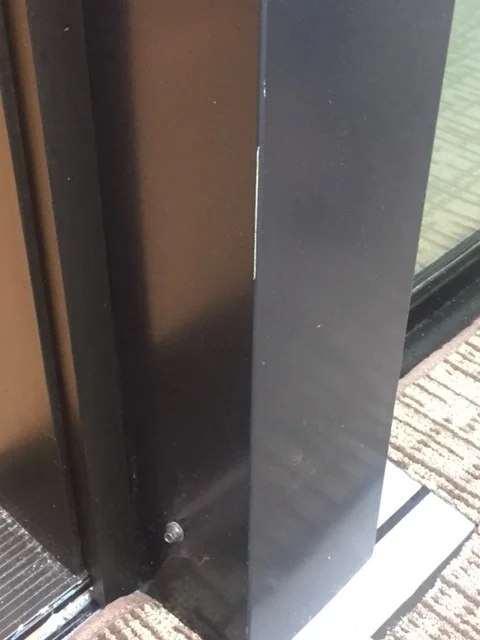

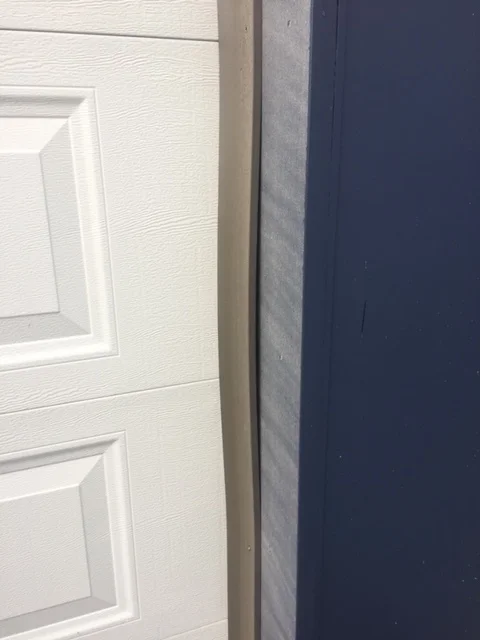

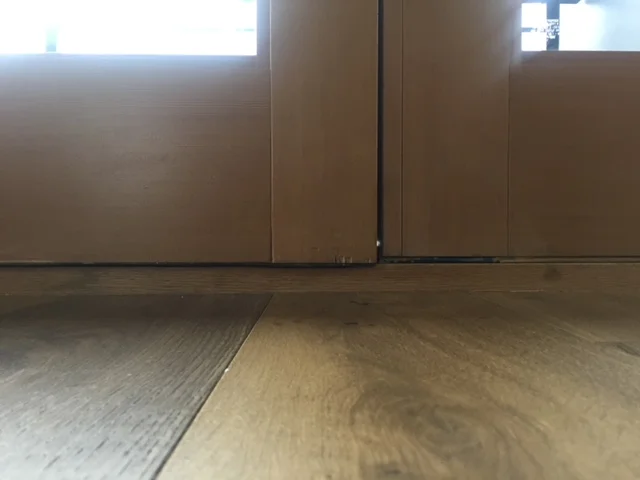

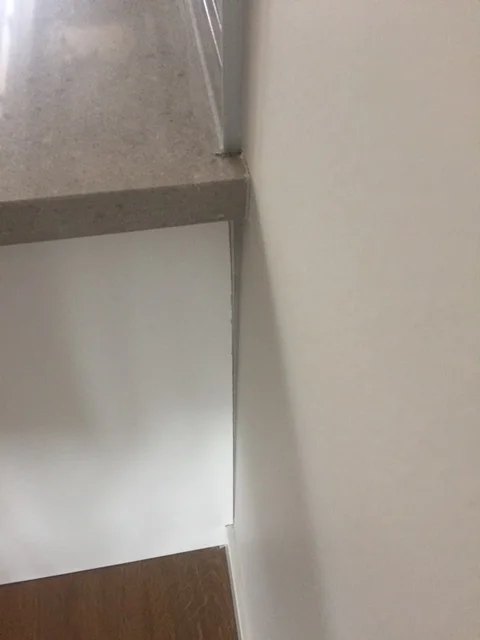

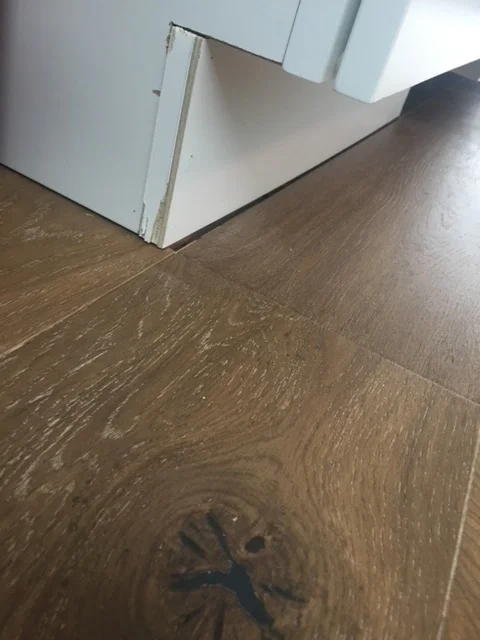

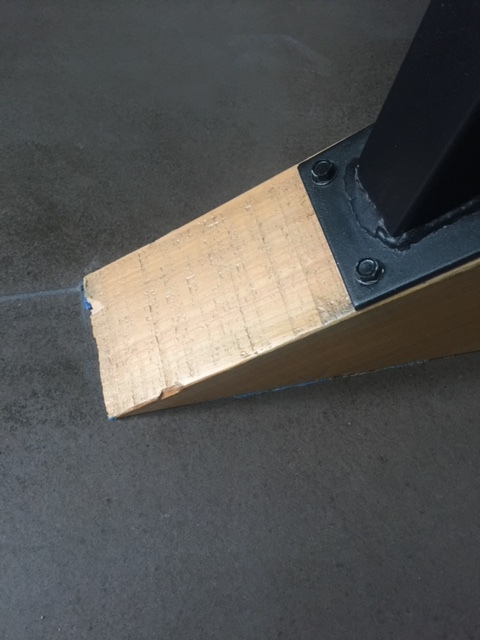

Below are photos of a project where the builder did not complete the work according to the drawings or ordinary construction protocols. These items were found during construction, and the builder was held accountable for fixing them. Again, these are photos of new construction that a builder called “complete,” and the builder tried to make the client pay for this shoddy work.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help

scuffed metal column wrap and gap in siding

new deck and new column, but nowhere near being straight

unfinished drywall work

Poor quality cabinetry

poor quality cabinetry

major gaps in construction

door not installed with a plumb frame

door not installed with a plumb frame (see the uneven door hardware)

door not installed with a plumb frame

huge gap under door

Scratched metal detail and cut too short. No caulking

poorly fitted metal detail

Missing metal flashing due to poor construction sequencing

broken siding and rough cutting

More broken siding

no caulking on outdoor electrical fixture

vent not attached (my 2-year old pointed at this and said “uh oh”)

No grout or baseboard

poorly fitting panels, poor caulking, and rough cuts

Only part of the door trim painted on right side

Poorly fitted gasket/weatherstripping

missing siding

Huge gap in siding

Rough cut siding and poorly fitted (this is what you see while walking to main entry)

that’s not pretty (again, this is a new house!)

custom blackened steel hardware, but installed off center

completely unsafe stair stringer attachment (the builder just threw in the towel on this one). Each is hanging by a nail.