This is the most boring post I have ever written, but if I asked you to read it, please do. Thank you:)

As an architect, above all else, I need to do the right thing when it comes to designing buildings to ensure they perform well and are safe. The buildings architects design have a huge effect on how people live, work, and experience the world around them.

The building code is really a collection of different ambiguous books that govern the design and construction of fire safety systems, electrical, plumbing, structure, mechanical, energy conservation, and more.

If you read the codes, you will rarely find any language that exactly pertains to your situation, so the architect must propose a plan that the building department must review. The interpretation of the building department and architect do not always align. An architect could read a code and interpret it in the complete opposite way of the building department. This is partially because the building department takes a conservative approach to make things as safe as possible. This is easy for the building department since they don’t have to pay for safety features like fire sprinklers, fire-rated walls, fire detection systems, multiple exit routes, backup power supplies for exit lighting, etc. These are all expenses that most building owners do not want to incur. Sure, building owners and architects both want their buildings to be safe, but there is a certain level of common sense that should be applied.

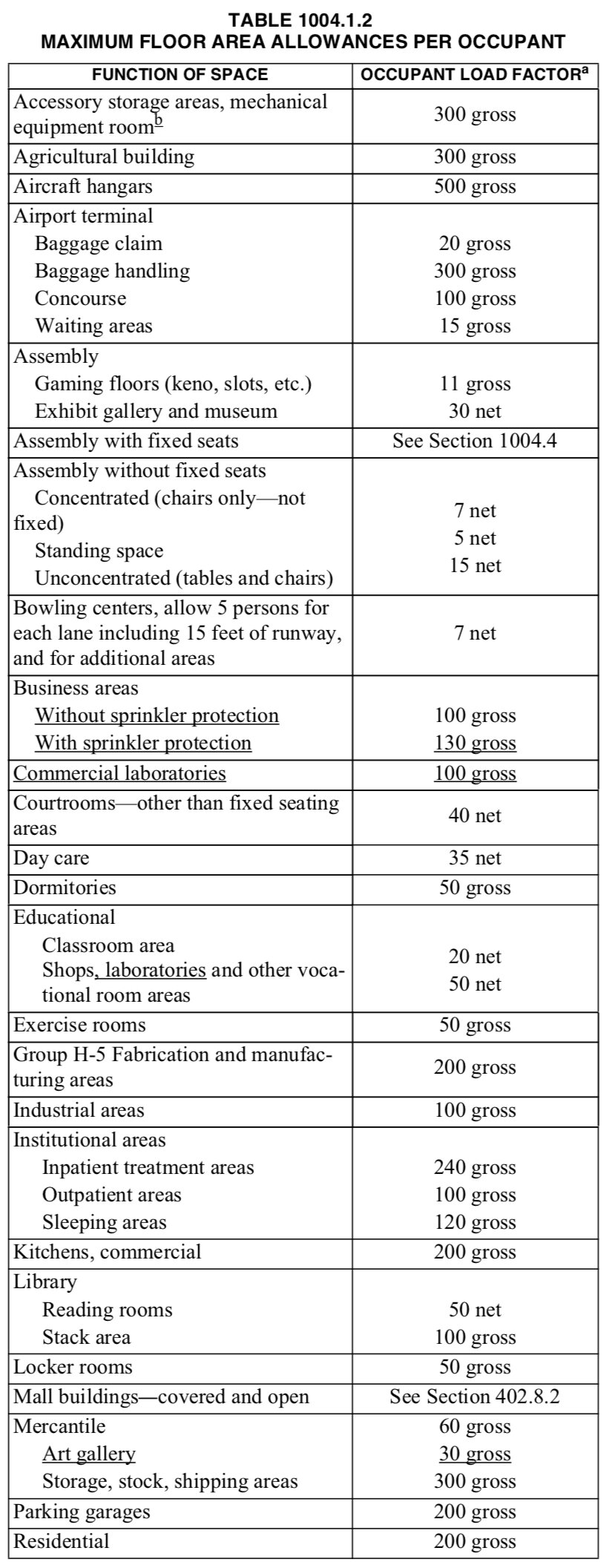

An architect is very good at recommending, interpreting, and negotiating the way codes get implemented. One major code issue stems from the number of people, known as occupants, that are allowed in a space or an entire building. Codes vary from place to place depending on many circumstances, but generally speaking, an office space may allocate 1 occupant per 100sf, but a waiting area may allocate 1 occupant per 5sf. Therefore the waiting area can fit a lot more people than an office, but this is not necessarily a good thing. If a 100sf waiting area fits 20 people (100/5=20), and a 100sf office fits 1 person (100/100=1), the total number of occupants allowed is already up to 21. Once you add up the occupants allowed in other rooms, the number gets even higher. In many cases, if the occupant load (number of people) exceeds 49, then you may need to add another exit door or potentially fire sprinklers depending on a few factors. That may not be possible financially or technically from a space layout point of view. Not only does the number of occupants affect the number of exits and sprinklers, but it also dictates the number of toilets, sinks, drinking fountains, parking spaces, hallway widths, and many other factors. In light of this, there is incentive to keep the occupant total lower. This results in strategically designating spaces, so the math for occupant load works in the client’s favor. By calling a space the wrong thing, it could trigger some very expensive construction requirements that could become project stoppers.

As an architect, I can be a very helpful guide to ensure you get a safe, functional building within reasonable limits.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help