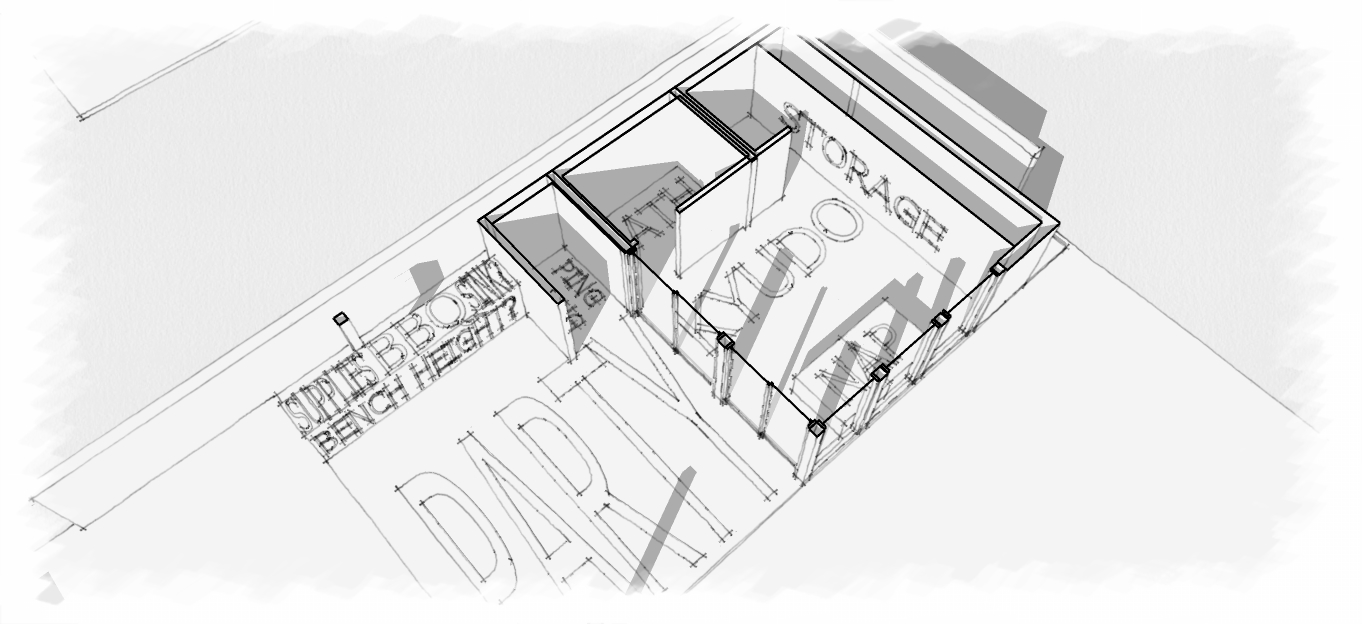

I walked into the building department with the intention of getting one of the most simple building permits I have ever had to get: an STFI permit, or a "stiffy" as we call it in the trade. This stands for "Subject To Field Inspection." It's a permit where the building department just hands you a permit "over the counter" for a project that's so small in scope that there's barely anything for them to check into. This is much better than waiting months for them to review your plans. I was helping a builder/friend get the permit to finish out a portion of his brother-in-law's basement to someday use it as a rental. This is called an ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit).

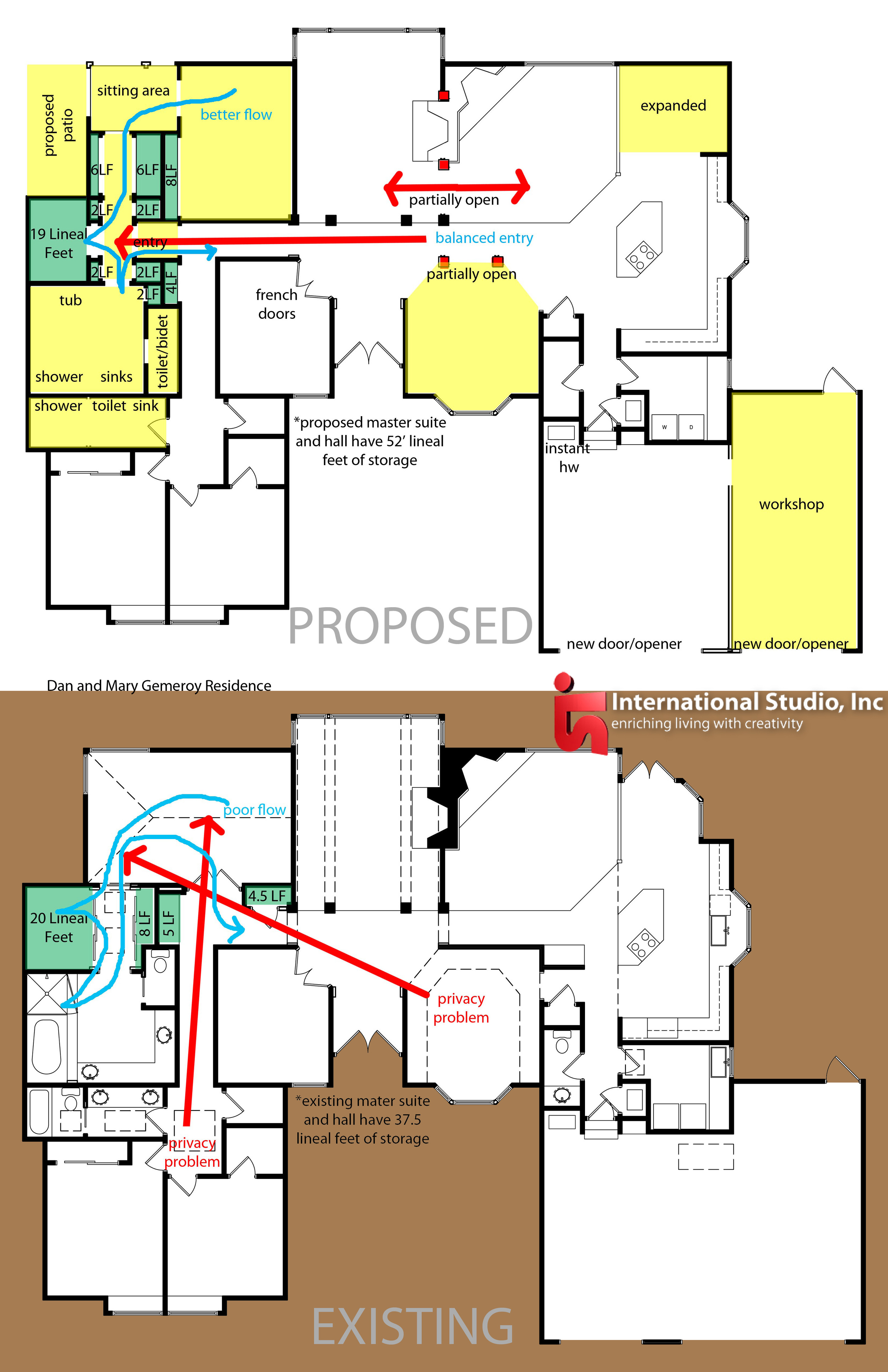

I knew going in that ADU's don't qualify for stiffys. I also knew that you could rent out a non-approved ADU and not be fined as long as you submit the ADU paperwork within one year of using it as an ADU. So my approach was to design the space as ADU, not call it an ADU (yet), take advantage of the quick/simple stiffy permit process, and later fill out the ADU application once the client was ready to actually begin using it as an ADU once construction was complete (pursuant to all the regulations and policies the building department has in place).

Upon turning in the drawings, the building plans reviewer quickly said, "this won't qualify as a stiffy since you're doing an ADU." I said, "it's not an ADU. It's just additional living spaces in the basement accessible to the main floor - just as it always has been in this existing house." The reviewer said, "well, it LOOKS like an ADU, so it won't qualify for a stiffy." I replied, "I don’t care what you think it looks like…it's not an ADU yet, the goal is to turn it into one someday, it does not match the definition of an ADU yet as it is defined in the land use code, and it does not matter what it LOOKS like - it matters what it IS." The reviewer responded, "I'm getting my manager."

After awhile, the manager arrived and engaged in some small talk with me. We discovered we are both from Ohio, we played hockey in some of the same ice rinks, and he asked which city I'm from. I said, "Youngstown." He said to his coworker, "Youngstown. Ok. This guy is tough. He's not leaving here without a permit." Next he asked me, "what's the problem here?" I told him, "this guy cares more about his opinion than he cares about enforcing the codified ordinances of the municipal code which is the sole purpose of his job. I'm here to follow the rules. The rules say my client is allowed to get a stiffy. The rules say my client is allowed to convert this project to an ADU whenever he wants. The rules say you can't fine my client even for illegally using his project as an ADU as long as he fills out the paperwork within one year of doing so." The reviewers glanced at each other and then at me. The manager said, "cross off the kitchen appliances from the drawing and process his stiffy. Expect him to fill out the ADU form within a year."

Growing up in the rust belt of Ohio set the tone for this interaction. The manager knew I beat the odds to come from one of the fastest shrinking, crime-ridden cities in the country. Youngstown has been a depressed area since its prominent steel industry moved overseas decades ago leaving many of its residents without jobs. My dad and his dad worked in those steel mills. Lucky for me, my dad put himself through school at nights to make a better life for himself and for me. This work ethic became part of my DNA. The building plans reviewer knew I had overcome much bigger problems than getting a simple permit, and he knew I wouldn't accept “no” for an answer just to leave with my tail between my legs. I must admit that coming from a tough town does make you stronger. I don't expect anything to be given to me, and I expect to work hard for everything that I have. I'm thankful to have earned this work ethic.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help