During construction clients commonly ask me, “Why would I need the help of an architect during construction? Can’t the builder just build from your plans?”

This does not work, and the following photographs prove it. These photographs show what can happen when a builder refuses to involve an architect during the construction process. This builder believed he did not need the oversight and guidance that the architect provides. Had the architect been invited to review the work regularly during construction, these problems would have been avoided. There are also additional problems not depicted in these photos of inadequate structural framing issues that are causing the house to move. This builder believes his work is high-end, high quality construction. This is not true, and consequently he is currently involved in a lawsuit to repair the work to be compliant with the requirements of the approved contract drawings. I believe these photographs speak for themselves. (Remember, this is a NEW house.)

Rough siding cut with no reglet

While trying to fix an improperly installed balcony, the builder damaged the siding. Two wrongs don't make a right.

Poor tolerances

This was a custom sized steel balcony. It could have been built to the exact dimensions needed. The builder did not send the as-built dimensions to the architect to enable the fabricator's shop drawings to be verified. Consequently, a stack of washers had to be used to fill the gap. Even worse, there is nothing behind those washers except for 1/4" thick siding. The bolt is supposed to go into solid wood blocking. That blocking was not installed behind the siding, and this balcony, siding, weather barrier, and plywood substrate will need removed and replaced, so the balcony may be properly installed.

Careless craftsmanship

Again, two wrongs don't make a right. In fixing one area, the builder cut the siding (poorly), and re-installed it. A new piece of siding should have been installed here. Or at least he could have put a reglet reveal to attempt to match the rest of the house and disguise his shitty work. (Pardon my language - I'm getting fired up while writing this). THIS IS AT THE FRONT DOOR TO A NEW MILLION DOLLAR HOUSE! IT'S THE FIRST THING YOU SEE!

Poor craftsmanship

Another result of the previous photo.

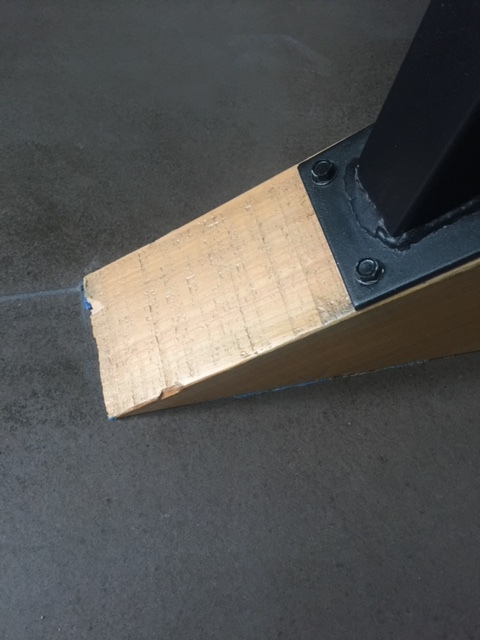

Non-level stair treads

The builder installed the bracket improperly, and the stair tread ended up non-level, in both directions. At least he noticed it and tried to fix it. The fix was to add a shim (which is fine), but it prevented him from easily putting in the bolt needed to secure the tread in place. So he just didn't add the necessary bolt, and now the stair is quasi-safe (if there is such a thing).

Wrong concrete finish

Do you notice the sheen on the bottom tread? I do. That tread is not brushed concrete as specified like the rest of them. They were specified to be brushed concrete for safety. The builder dropped a concrete tread, it broke, and he ordered the wrong type of replacement. This happens. We all make mistakes, but two wrongs don't make a right. When you walk up these stairs, you can feel the grip of the brushed treads, and you expect it. On the bottom tread, you also expect the friction, but it's not there. Someone will slip someday.

Door threshold problem

This door threshold does not extend beyond the side of the building and leaves the weather resistant barrier exposed. This is the front door! This is what you see upon entering a million dollar house. There should have been trim to cover that area, and the door threshold should have projected beyond it for positive drainage onto the perforated grating on the balcony. Also, the builder left the blue tape for the homeowner to remove.

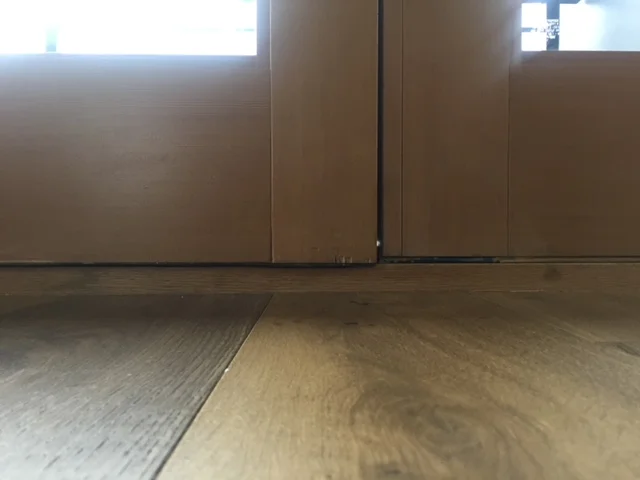

Threshold craftsmanship problems

This is the threshold at the main entry of a million dollar house. It was not protected during construction or securely installed. Notice the gaps between the interior and exterior. Every aspect of this is rough.

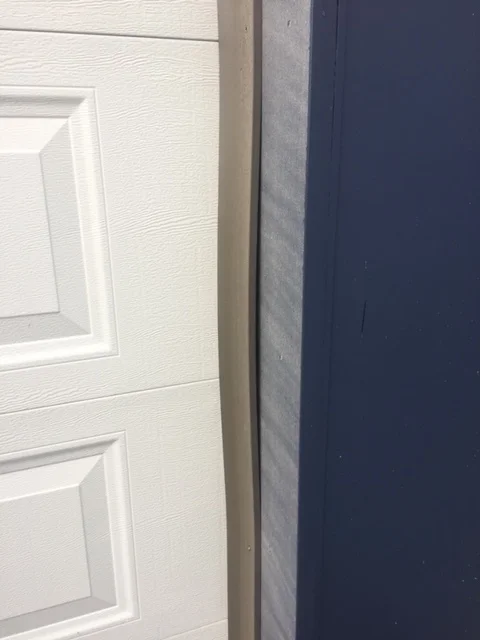

No weatherstripping at door

This is the front door. It has a high-tech ventilation system to enable air, dust, insects, rodents, and evil spirits to enter without a problem.

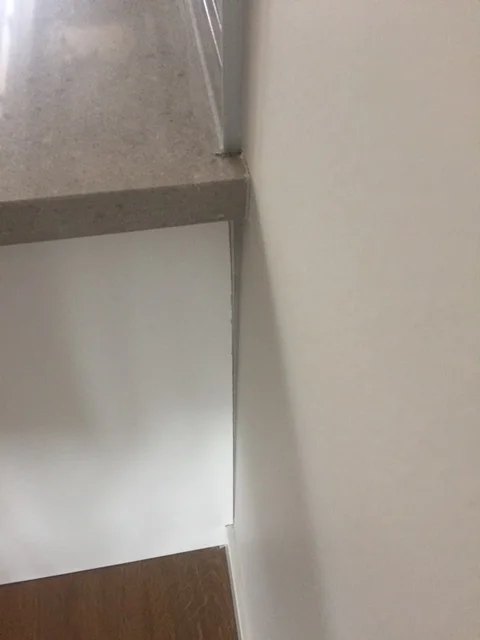

Mis-cut tile

The tile was improperly cut, and now the mortar is exposed at the front entry. (Also the extra bumpout of drywall was not supposed to be there at all. The door was supposed to abut directly against the wall. The builder re-built this two times and still got it wrong.)

Scuffed column wrap

This metal column wrap at the front entry is scuffed. This happens. Construction is a messy job, and things get bumped. Perhaps try doing a paint touch up, or protect this vulnerable area at the front door, or even better - remove and replace this $50 piece.

Inadequate caulking and careless craftsmanship

This is a photo from a home in the war-torn region of Aleppo. No, this is a new home in Seattle. This connection between a window flashing and metal column wrap is not only scuffed up, but it is also not filled with caulking. The builder tried to fill it with caulking but failed. This is careless. This will leak. The framing behind these parts will get wet, rot, and potentially develop mold, mildew, and fail.

Rainwater catchment debacle

The building code requires rainwater to be caught on the property and dispersed slowly on site instead of just being directed into the sewer system. There are calculations for how much water needs to be contained. The builder did not consult with the architect on what type of catchment system to install. He just showed up with this flimsy steel box resting a few inches under ground. Besides it looking bad, it also covered the basement windows. After the architect explained that any overflowing water would seep into the basement windows, he cut openings in the steel to enable any overflow water to flow out of the container. This defeated the purpose of having the container at all. The container was required to be over two feet deep to contain the required volume of rainwater. Now that he cut the openings in this eyesore, it only holds a few inches of water. Communication is key. This should have started with a deeper hole (and shoring as needed), shop drawing approval from the architect of the steel fabricator's plans, and accountability for the outcome. This builder simply did not care, and now there is a flimsy, useless container in a hole in the ground that obstructs the side yard.

Gaps in siding

The metal siding is not touching the rest of the siding. This leaves the weather resistant barrier and wood furring strip exposed. This will rot, deteriorate, and cause more significant problems.

Missing siding

The siding was supposed to be installed in this area to cover the roof to wall connection. Also, that thin strip of vertical siding was supposed to be a wood column.

Door casing not properly attached

This liner in the door casing is not properly attached. This is an easy fix, but a builder needs a basic level of craftsmanship to notice it and accountability to followup on it.

Incorrect siding pattern

The joints in the siding pattern were supposed to be centered on the garage door. They are off-center. You can also see the wobble in the door casing on the right side of the door.

Water and electricity don't mix

According to the manufacturer's instructions, caulking is supposed to be installed here to fill the void. Water will get into this junction box and short out the circuit. This can cause a spark and a fire.

Rough craftsmanship

The edges of this siding are cut quite poorly. A sharp saw blade (intended for this material) and a straight cutting edge easily prevents these problems. The bottom of this siding panel is also flaring out which indicates it was not properly attached.

Improperly attached vent

This exhaust vent is not attached to the wall. This should be fastened with screws, caulked to prevent moisture (and insect intrusion), and a cover should be installed (to prevent rodent intrusion).

Poor workmanship

I'm not sure what to say here. This is a thin piece of siding. It is flimsy to work with, and it broke when nailing. This is tough to deal with, but it can be dealt with. This could have either been pre-drilled before nailed, or it could have been spackled prior to painting. Neither was done, and this will be an area where water leaks in, the siding gets saturated, and it will eventually fall off.

Broken siding

The builder likely dropped the siding panel when installing it or removed a nail and chipped the panel. Either way, this is someone's new house, it is a reflection of a builder's craft, and it should have been replaced. The nail pops also indicate a lack of craftsmanship.

Incorrect trim

The contract drawings stipulated a mitered wood corner condition. This enabled a seamless wood box. Instead the builder did not want to take the time to miter the corners, so he covered them with a blaring white plastic trim piece. It took a substantial amount of convincing to get the builder to paint it black to at least match the windows. He painted it blue. Sigh. The builder never credited the owner for this change in scope.

Misaligned door hardware

Notice how much higher the right door hardware is than the left? This door takes quite a bit of effort to close properly. It has the character of a hundred-year-old house, but this house is less than a hundred days old. This is the result of the builder framing the structure of the house incorrectly. Consequently, the house is moving, and this has brought this door out of alignment. The hardware has been adjusted several times, but it cannot be resolved. This area of the house will need to be reframed. Yes, all the siding and finish materials need removed, and the house needs rebuilt in this area. The problem goes beyond a misaligned door. The seismic support structure was inadequately constructed, and this is a safety hazard. The builder did not follow the plans, and he did not follow the fixes offered by the structural engineer after the problem was discovered during inspection. The builder "faked" the installation of certain hardware to pass an inspection, but the lateral structural system was not properly installed. It was later discovered that the builder did not know how to read drawings, and he had too much ego to ask for help.

Misaligned double door

This is the same problem as the previous photo. Notice the left door is lower and bulging inward. You may also notice the floor sloping downward to the right. This is a result of the improperly framed structure of the house.

Misaligned double door

This is the top of the door from the previous image. Notice the right door is higher.

Unsquare door opening

The framing of this door was built out of square and/or has moved since the house was not built according to the structural framing plans. Notice how the bottom hinge is buried inside the drywall and the top hinge is completely outside of the drywall. Either the wall is tilted or the door is tilted. This should not happen in a new house. (This is the same problem as the previous photo).

Out of square

Which is angled - the cabinet or the wall? The angled caulk joint shows the top portion of the white cabinet is not touching the wall. I would not be surprised if the wall was built at an angle.

Poor quality cabinets

These are the high-quality custom cabinets that the builder insisted he would build in-house instead of subbing out for a cheaper lower quality alternative. The toekick was installed without care and left unfinished. It turns out the builder did not build these cabinets and did sub them out to a cheap manufacturer. The builder marked up the price of the cabinets by over 400%.

Poor quality cabinets

This is the same problem as the previous photo. The trim is also inconsistent with the previous photo.

Rough backsplash transition at window sill

This is where a backsplash meets a window sill. A tiled sill was requested here, but instead, the builder left the drywall in rough condition without any trim over the mortar.

Beam patch problem

This was a very long and very expensive beam. It had to be shipped on a train from Canada. Wood has irregularities, and that is ok. This builder patched a chip with white filler. It would have been better to leave it unpatched or to match colors. It would have been best to protect the beam during construction to prevent the chipping altogether.

Misaligned bracket

This was a custom fabricated bracket to attach a very cool (and expensive) wood column to a wood beam. The builder did not get approval of the fabricator's shop drawings from the architect. The bracket was also installed too far to the right. A tape measure would have been an effective tool in getting this installed on center. A torpedo level could have also helped install it straight, so it is not leaning to the right.

Stair stringer problem

This stair stringer was not supposed to project at an angle to the floor. It was designed to be cut vertically at the bottom of the stair. This is a tripping hazard and looks bad.

Stair stringer problem

Same issue as previous photo.

Poor stair craftsmanship

Stairs are difficult to build. There are a lot of custom parts and pieces that need careful attention - especially at the main sculptural stair at the dramatic entry to a custom home. The shop drawings for the railings were not given to the architect for approval. The holes for the screws were not filled (and they should not have been there anyway). The stain from the column leaked onto the stair tread. The stair stringer has chips. The landing is not scribed (or filled) against the column. This is a messy display of craftsmanship from a builder who claims he only does high-end custom work.

Flooring gaps

The flooring was not cut tight to the column. We requested the builder to fill it. He did it! Victory. I would expect the builder would want to do this without being asked though.

Scuffs and gaps

Here is a scuff on the metal column wrap and a gap between it and the siding. The column wrap was supposed to cover the siding gap. The weather resistant barrier is exposed, and water will leak into this area. This will cause further, more severe issues.

Misaligned column wrap

Is this column wrapped attached straight? Nope. Whats that extra hole in the decking? This is possibly acceptable in a low quality build, but that was not the case here.

Misaligned column wrap

Is this one straight? Nope. 0 for 2.

Misaligned column wrap

Is this one straight? Nope. 0 for 3. Reminder - this is new construction. There were no existing conditions to work around that would require compromise.

As you can see from these photos, it makes sense to have frequent oversight during construction. Commonly, clients attempt to save on design fees by not involving the architect during construction because they believe it is an extraneous expense. With oversight during construction, we can prevent these problems and spot them before they become bigger ones. We also come up with friendly solutions (compromises) that work for everyone's agenda. In some situations, rework is necessary, and credits back to the client are required. A solid team between a builder, architect, and client is essential to keep the communication open, so effective and efficient decisions may be made in real-time. Fixes after the fact are messy, expensive, and difficult. The builder who built the items shown here is now involved in litigation and is being held responsible for the items that he built below the standard of care that is ordinary for the industry and for items that are not built according to the drawings. This builder was negligent in seeking guidance and approvals during construction to enable a good outcome. Thorough vetting of builders is also important. In busy construction climates, lower quality builders seem to emerge since the good ones are busy, and the cost of everything is going up. Taking a step back and evaluating all possible avenues is certainly worthwhile. In this situation, the client will end up being compensated for the builder's negligence, but nothing will ever compensate for the stress and added time that this causes.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help